Although we speak of individuals who are uniquely achievement oriented (AO), this quality is not—other than perhaps by some measure of degree—unique. We are all achievement oriented. And all seems to include plants and micro-organisms. On some level, every organism is beset with challenges to survival. And the organism must achieve a modicum of satisfaction of some objective or objectives within its milieu to survive.

Within the general and broad scope of achievement, we humans are versed in terms like objective, goal, reinforcement, motivation, encouragement, prodding, reward, punishment, merit, demerit, success, failure, and others. Much study is devoted to this area, and our technology depends on methods to maximize and maintain both personal and collective quantitative and qualitative standards.

These standards are spoken and unspoken. A patient’s surgeon may silently note success at the patient’s achievement to evacuate his bowels after lengthy anesthesia, while Lindbergh is awarded a ticker tape parade in New York City for his transatlantic flight.

Obviously, exercise depends upon motivation. And as Arthur Jones said, “You can’t push with a rope.”

In other words, you can’t motivate someone who wishes otherwise (unless you resort to socially unacceptable means—threats, physical abuse).

[Arthur also asserted that the most consistent motivator is fear, although fear might produce unwanted and unpredictable outcomes.]

And motivation requires some kind of achievement orientation. The problem, though with exercise, is that the orientation is obscure. It’s not obvious. And it is easy to mistake the desired objective (explained below) with something which the exercise subject is already familiar and obvious AND erroneous. This other something is a deception.

This leads the exercise subject to associate success with the attainment of the other something as some kind of obvious performance objective like force magnitude, distance moved, or a time measurement.

A similar problem exists in other fields. In mastering the trumpet, it is natural to become consumed with achieving the highest notes or mastering a technical passage. These are worthwhile objectives, but they may obscure the general purpose which is to make the sounds musical.

In learning chemistry, it is natural to become consumed with making the lab work agree with published standards when the real goal is to accomplish an understanding of bonding and other interactions so that this understanding can be applied to produce chemical products.

I was told by a physics professor that some of her students acquire a high score on their tests merely due to their mathematical prowess while some math-challenged students show a deeper intuition of physics principles. [Example: Ask a student to explain the practical difference of kinetic energy (KE = ½ mv2) and momentum (p = mv) with the observation that mass and velocity are factors in both equations.]

AO is figurately hard-wired into our beings. And this orientation can be in the physical as well as in the intellectual realm—not to deny that some intellectual achievements (i.e., music) often involve demanding physicality and that some physical achievements (i.e., sports) involve great intellectual aspects.

To repeat, the degree of AO in humans varies widely.

Major Dependencies of Exercise Instruction

With exercise (defined at the end of this article) and as an exercise instructor, I am beset with the challenge to motivate an exercise subject. Where do I begin?

Note that I am challenged to challenge the exercise subject, another person. To a degree, his achievement is dependent upon my achievement.

And before I can achieve my objective, I must be armed with an exacting objective for the exercise. Therefore, I must achieve a working definition of the notion of exercise and have a plan for its execution.

But there are actually more levels to this than two, depending on how we divvy this up. To begin with, I will have a foundational (definitional) challenge (the primary challenge) with which to convey guidance language (the secondary challenge) with which to motivate the subject (the tertiary challenge).

Is it possible for me to be so versed in the definition that I can couch it into a verbiage and context (conveyance language) that is intellectually seized upon by the subject to encourage his effort toward correct performance? To do this, I must assess the exact level of the subject’s understanding for my conveyance language.

Assumably, it is not practical, on the fly, to provide deep technical background in the midst of an exercise set. Hence, the language therein must be restricted to the terse cues and signals required for execution of the exercise(s).

Outside of the exercise set (preferably before), more elaborating detail must be settled between the instructor and the subject.

Can the instructor assume that the subject has a modicum of understanding? Is the subject on par with the instructor’s operational requirements? Or must the instructor start from scratch and build the subject’s understanding?

Or has the subject been elevated to a modicum of understanding but continually forgets important elements and must be renewed to that modicum?

This is a lot to ask of me… or of anyone whose ambition it is to be an instructor. It requires much more than barking out you-can-do-it platitudes.

As you might appreciate, motivation of the exercise subject has several overlying dependencies. And if I (as his instructor) fail at one of these dependencies, I am likely to fail as an instructor overall.

In fact, if the subject grasps the essence of inroad in exercise despite my incompetence, it is due to the subject’s high intellect and awareness of the objective and personal motivation OR a very unlikely accident.

Orientation, Orientated Achievement

When I hear it said that a person is “achievement oriented,” I immediately interpret this to mean that the person is bent on achieving something. This isolated statement rarely specifies exactly what it is that the person is enthusiastic to achieve… just that the person desires achievement of some kind. Of course, this is usually explained within the context of a broader conversation.

But let’s examine orientation more deeply.

To orient means to point or to face or to go in a particular direction or to aim toward a particular target. And achievement orientation (AO) is much different in meaning (not merely in syntax) than oriented achievement (OA).

This is the crux of comprehending the real process and the desired objective of [an] exercise (see the blue flow graphic below). This eludes almost all exercise subjects as they are often maloriented, even though they may possess and exhibit high AO. In other words, these highly driven subjects are highly driven in a mistaken direction. They are trying to excel with the incorrect process to hit the proverbial bullseye on the incorrect target.

An exercise subject who is highly AO but who is maloriented in their pursuit of an erroneously imagined achievement will waste time and incur unnecessary danger to themselves and sometimes to others.

Above, the red flow chart of The Assumed Process ends in the Fantastical Purpose. We usually place No Purpose in this box to represent that the purpose is wildly ill-conceived or not conceived at all. Herein, I make the exception with Fantastical to emphasize in this discussion that the purpose—if one is imagined—is often wildly exotic and unrealistic. It borders on the insane. [I direct you to Reconfiguring the Real Objective for an in-depth explanation of these two flow charts.]

When I was a teenager and young adult, I harbored the most asinine notions of what exercise was going to do for my body. And I really was ahead of my peers with my approach to exercise at that time as their notions were yet more delusional than mine. Reflecting on these fantasies, I know that people, even otherwise intelligent and mature people, buy into these inane dreams. I avoid recounting mine as they are truly embarrassing.

Dreaming is sometimes useful. But dreaming, even mere daydreaming, is mindless. And with exercise, mindlessness must be avoided. [I find the nuance between mindless and thoughtless interesting. I wonder how much difficulty those of foreign mother tongues grapple with this distinction.]

However, imagination is a useful and necessary tool for a targeted ambition, but the imagined target (imagery) must be correct.

The role of imagery is what the famous photographer, Ansel Adams, termed visualization. He used his metered calculations of the light ranges of his selected scene as they were affected by the momentary weather along with his knowledge of the properties of his chosen film emulsion, the film processing delimitations, his skills at dodging and burning, and the properties of the printing paper to effect what he saw in his mind’s eye BEFORE he clicked the camera shutter. Many people view his prints with awe at their apparent reality when the images are not reality at all. They are the preconceived images of Adams’ mind.

An exercise subject must visualize—not manipulate scenes of reality as did Adams—the real process that we know as inroad. Inroad is the momentary fatigue caused by the effort of the subject. And for the most part, inroad must be imagined, i.e., visualized.

And while Adams’ photographic visualization was the completion of a long series of technical controls—in other words, a complex intellectual gymnastic—visualization for inroad is relatively simple. Or at least, inroad visualization can be accommodated to allow for simplicity.

And in practice—once the subject is acquainted with the overall objective and purpose depicted in Gus’ blue flow graphic—the actual execution of each exercise is very simple, especially with static exercise. Dynamic exercise is much more complicated, but it can also be drastically reduced to manageable elements in many cases.

And why is it necessary to visualize inroad?... because it is blind.

While inroad is far from being illusory, it cannot always be easily seen and measured. Sure, this momentary fatigue can be experienced by feel AFTER the exercise bout, but it is not a thing seen or heard or tasted or smelled or truly felt during the inroad process, at least not with a static exercise incorporating no feedback (TSC).

Without the feedback of a measured weight being lifted or a force metering of some kind, your senses may alert you to the burning of the involved muscles, the depth and rapidity of your breathing, the vibration of your limbs, the increased heat of your body, your increased pulse, but the fatigue (reduced force output) is not truly perceived during the exercise, especially with static exercise.

Very strong men are convinced that they are just as strong at the end of an exercise as when they began until they are shown the readout of a static exercise or notice that they can no longer lift the selected weight of a dynamic exercise.

A disastrous assumption that pervades the so-called fitness industry is that exercise is not nuanced. Indeed, many hard-core fitness enthusiasts assert opposition to the notion of nuance with slogans such as Just Do It. [How dare Ken Hutchins introduce nuance into exercise.]

On the contrary, exercise is extremely nuanced with linguistics dependency. And extremely AO people often embark into an exercise bout enthusiastically and energetically driven toward an erroneous destination devoid of the necessary nuance.

Blind Orientation

In the game, Pin the Tail on the Donkey, the chosen subject (child victim) is blindfolded and spun around to deliberately unorient him. Then he is challenged to pin a fabricated tail on the buttocks of a displayed image of a donkey.

I, like many, played this game as a child at birthday parties. I found it to be torturous and far from fun. In the midst of the child so handicapped, the other children are yelling and screaming and laughing so that he is encouraged toward the donkey by some and laughed at by others to the extent that he is timid to make a commitment.

The victim has no bearing as if a compass when placed at the North Pole acts erratically and can provide no certain direction.

When a bit older, these children—as young adults—may play a game of football wherein a ball carrier becomes disoriented and DOES commit. Amidst the crowds jeering and cheering, he commits all his will and physical strength to making a score, but to the incorrect goal line and for the incorrect team. This safety (the term in this sport) is very close to what I mean by disoriented achievement in exercise. And though this disorientation is relatively uncommon in the game of football, it is very common in exercise. It’s almost universal.

Different from the victim in Pin-the-Tail-on-the-Donkey who is UNoriented, the footballer is DISoriented. The victim of the child’s game has no bearing while the footballer has bearing, though incorrect bearing. They are both MALoriented.

Which is worse—unorientation or disorientation—is a matter of perspective.

Again, the child victim playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey was completely unoriented. I liken the general fitness enthusiast to this state as he simultaneously engages in a host of supposed conditioning activities as:

Cycling and/or jogging and/or swimming for so-called cardio conditioning and so-called bodyweight control

Stretching for flexibility at the expense of stabilized joints

Light weight training to build so-called muscular endurance

Heavy single-attempt and explosive weightlifting to build so-called power

Boxing to build so-called general skill, another myth

Tai Chi to build balance that does not transfer to other activities

Doing Pilates to develop mythical long muscles

He exhibits mixed direction towards fantastical goals as he has no bearing, somewhat like the erratic compass described earlier.

Again, the young adult playing football and charging toward the incorrect goal exhibits DISorientation. He aims at a target, but it is the incorrect target. His behavior is akin to the typical, serious weight-training enthusiast. Although the weight-training enthusiast focuses correctly on muscular strengthening to the exclusion of the other nonsensical conditioning activities, he still harbors the erroneous externalization habits ingrained with making the exercise apparatus perform rather than making his body perform.

In other words, he is committed to becoming stronger just as the disoriented footballer is committed to scoring a touchdown. And like the footballer assuming that a false pathway leads to scoring, he is deceived that a false process will lead to greater muscular strength.

Both the real process and the desired objective are obscure. It is a blind process that requires imagination, but the imagination must be the correct imagination… the correct visualization. The typical exercise subject performs without any visualization. Again, it’s a mindless affair. Sometimes it’s more of an exhibition... even to himself.

To a great degree, some of the obscure elements (not the desired objective) of an exercise bout can be seen with the feedback statics (FS) exercise equipment represented next.

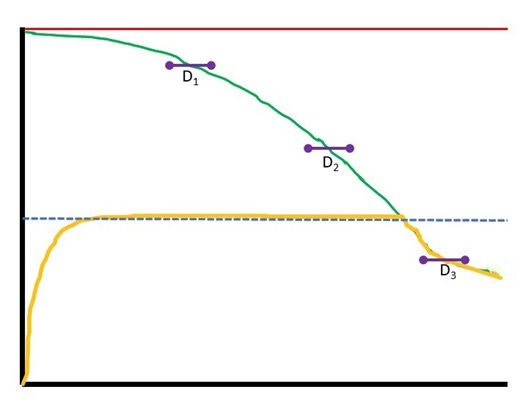

In Graph #1, I depict an exercise performed with FS incorporating an analog interface that provides real-time performance data with historical view. Historical means that the subject leaves a trail (a trackway) behind his performance that can be observed, studied, and recorded for future review. This aspect can be seen by the subject on a monitor.

This graph illustrates the various aspects of an exercise performed for a muscle group in a 90-second bout of continuously meaningful load.

The vertical black line represents the Y-axis for force; the horizontal black line represents the X-axis for time. These aspects are visible.

The dashed blue line is a target load drawn on the graph for the subject to target by applying force to the apparatus; the subject’s efforting and generated force scribes the gold line from zero up to just slightly more than the dashed blue line (target load). These aspects are also visible.

The green and red lines respectively representing inroad and certain injury are invisible. The space (distance) between the red and gold lines is the safety margin.

The desired objective(s) is D and shown as a horizontal line colored purple. D is not only invisible; it is elusive and mobile. In other words, it’s hard to get at and it moves as the novice may attain it with shallow inroad and the veteran may require deep inroad. Thus, D is for depth at levels 1, 2, and 3.

The red and green lines are extremely important for the subject to heed, although they are not visible. The green line’s decent represents the real process: inroad. The red line represents the highly hostile event of injury to avoid. [The benefits of the green inroad line are explained in Critical Factors for Practice and Conditioning.]

If these two important lines cannot be seen, they must be visualized. And this visualization is only possible with the exacting language and the use of graphics.

In the case of Graphic #1, we are considering the visible as opposed to the invisible when the exercise is performed on an apparatus that offers feedback statics. [Such information is relevant to dynamic exercise, but dynamic exercise does not lend to such feedback during performance.] The feedback equipment, especially that with analog feedback, can reduce the number of invisible elements and serve to greatly simply the instructional conveyance.

In a case without feedback (i.e., Timed Static Contraction or dynamic SuperSlow exercise) those aspects represented by the blue target line and the gold performance line are also invisible.

Therefore, excepting a time measurement, at least two of the elements of FS exercise are invisible and all the elements of non-FS static exercise (TSC) are invisible (except for perhaps time).

For the more common situation wherein feedback is not available, please read the book mentioned above and watch the video: Timed Static Contraction Exercise for Hip Rehab (time code: 00:26:40 – 00:42:46). In this video, I emphasize the importance of a whiteboard presentation to first provide the subject with a mental framework with which to guide the performance of the exercise. This hand-drawn graphic is as important as the words that accompany it. The graphic is a crucial part of the linguistics although not actually lingual.

This mental framework—hopefully imprinted on the subject’s mind—is likely the only possibility that the subject has a reliable and simple guide as to what he is expected to do in the exercise. Without it, he is lost. Without it, your words mean little to nothing. Without it, both of you are pinning the tail on the proverbial donkey and are bearingless. Without it, the probability of injury is greater.

I emphasize imprinted as I regard this imprinted mental framework similarly as that concept of the ducklings described by Konrad Lorenz in his discussions of ethology. Without their mother, the ducklings fixated upon Lorenz when they first hatched and followed him everywhere as though he was a duck like them. Upon hatching, Lorenz was the first truth that they had. Lorenz was reality to them.

The desired TSC template as in the whiteboard presentation is a fixation of sorts, a beneficial fixation to guide subject’s performance in the exercise. Our challenge as instructors is to replace the subject’s innate and erroneous imprinting regarding exercise with this new one.

Again, I predict that an instructor will fail to convey the idea of TSC without the use of the whiteboard graphic. The lingual side of the linguistics will fail if used alone. However, once the graphic is successfully imprinted, all aspects of the exercise become ludicrously simple and safe—safe beyond passively lying in bed.

Lying in bed, the subject is not protective and not alert. During TSC, the subject is the opposite—aware and guarded.

I now regard TSC as more important than FS. FS does remove some of the mystery—especially when the graphical interface is supplied with a dynamic, historical plot. But so far, few facilities have this luxury, and many will never have it. And even with those facilities that offer FS, TSC remains useful and practical for subjects when they are away on vacation or if the FS is dysfunctional. Also, the FS is deliberately turned off in favor of TSC for some compromised subjects or for those who exhibit exotic discrepancies like surging.

Turning off the FS backfired on me years ago when a subject scolded me for “not raising her intensity” with the provision of the FS monitors. She insisted that the instructor’s job is “to keep up the intensity.”

I was surprised that intensity was in her working vocabulary, but more shocked that she failed to understand that how hard she efforted in the TSC was her prerogative and not in my control. I lost her as a client as I had failed to thoroughly imprint the TSC scheme in her mind. Yes, I had presented it, but I had not reviewed it as often as I should have, although I remember that this person showed obvious impatience when I reviewed material she deemed academic in the sense that it was merely theoretical gobbledygook that lacked practical value.

This woman was somewhat strident and indignant. Although an intelligent woman, her incessant references to experiences with sports activities exposed an arrogance that blocked her ability to see beyond her life references. She lacked a necessary humility to submit to learning.

Humility and Arrogance

Before now, I have not mentioned humility, although I have emphasized that to learn requires a kind of submission. I discussed this thoroughly in Critical Factors for Practice and Conditioning in my chapter about the four stages of learning.

We all start along a journey to learn a subject as students. Arrogance—the lack of humility—often prevents learning. At various stages in my life, I have been guilty of an arrogance that blunted my learning. This is a common trait among all of us to varying degrees.

We need to be confident with the knowledge we already possess for it to be useful in the acquisition of additional knowledge, but the danger is that there can be a thin line between confidence and arrogance.

Often, humility leads to knowledge. And knowledge leads to arrogance. And arrogance often blunts additional knowledge.

Also, arrogance does not often behoove the instructor. Except in the military where the training instructor has absolute authority, obeisance to an arrogant soul like Arthur Jones makes learning from such persons more difficult than necessary. [However, Arthur’s arrogance was usually deserved and necessary to overcome the outrageous arrogance of the ignorant bodybuilders and their unruly antics.]

Arthur often exhibited the ability to tone down his apparent arrogance to a level that was communicative. And it was often up to the student to determine that his submission to Arthur’s instruction was a worthwhile tradeoff for information he could obtain nowhere else.

Arthur asserted that although ego was often detrimental to learning, a man without an ego was feckless. Perhaps Arthur was hinting at what I am saying about arrogance. We can’t be sure. There are thin distinctions between arrogance, confidence, and ego.

We might characterize my previously described woman subject as a dumb cow. However, the following story might aptly qualify me as a dumb cow.

In a celebrated case filed with the Federal Trade Commission in 1936, Bob Hoffman (of York Barbell and Strength&Health magazine fame) called the dynamic tension of Charles Atlas (real name: Angelo Siciliano) "dynamic hooey." The case was dismissed.

Before being inculcated with Nautilus philosophy and my subsequent enlightenment, I mocked Charles Atlas for his [presumably fraud] dynamic tension. Now—after decades of reflection—I admit that perhaps his program was close to TSC and actually worked. I have no way to know, but I confidently assert that he (as well as his many critics) had no understanding of the real process. And my personal history regarding dynamic tension suggests that I had been a proverbial dumb cow.

When I developed the definition of exercise, I employed a blend of confidence and humility and arrogance. My arrogance was party to my conviction that the exercise physiology and medical communities were comprised of bumbling fools regarding exercise. This has not changed. But as I reflect on my apparent arrogance, I characterize it more as righteous indignation.

Developing the definition, my humility was in admitting to myself that I was figuratively whistling while walking through a graveyard. While I had the confidence that I was armed with information that was gleaned particularly via my association from Arthur Jones and Ellington Darden and coupled to my writing and processing ability, I might be concocting something that would turn out to be lame and embarrassing.

I privately admitted to myself that stating a definition risked casting myself as a pedantic fool. And while the definition—any definition—restricts the meaning of an utterance, boldly stating a definition of exercise would paint me into a corner that I could never escape. Fortunately, I decided to throw caution to the wind.

Still, when I state the definition, it is natural to perceive my delivery as arrogance. This is more probable as I usually assert that it is THE definition.

I do not believe that there is another working and workable definition for exercise, and I believe that people should take comfort in the fact that they need not muddle their minds with other possibilities. To do so merely wastes time and risks a pathway to injury.

Another reason that novices might hear arrogance when they encounter the definition is merely because it is new to them. This is a natural phenomenon. It’s a break with their proverbial imprinting (as I alluded earlier).

Information Alignment

I remember Arthur arguing with a physical therapist wherein the physical therapist was offended that Arthur was explaining points that were deemed for laymen and not for astute physical therapists. She regarded Arthur to be condescending.

As Arthur confronted her amidst a large crowd of mixed medical professionals, he explained that he was merely trying to determine her level of understanding so that he could tailor the conversation. She grew even more offended at his plea for her to tell him where to begin his presentation so that it was neither beneath nor above her level of expertise.

As instructors, we struggle to tailor our instructions to the level of the subject’s competence. It’s not a matter of rating a subject as a brilliant or a stupid person. We all have a particular level of grasp. And to determine and accommodate this level is another important aspect of the conveyance challenge.

Even when I talk to Gus Diamantopoulos—a man who understands as much or more about exercise than me and speaks fluently in our agreed parlance—the first words of a conversation are for alignment of the topic.

We both ask ourselves, “Is he talking about what I am talking about?” It sometimes takes several sentences back and forth to get us both going down the same track.

And such an alignment process cannot occur during an exercise set. It must, therefore, already exist before commencement of the exercise. Without alignment BEFORE the exercise, we are similar to a conversation with Gus that abruptly jumps into a fray of unanchored words.

For the many reasons explained, I now believe that TSC is the key to teaching exercise. FS is definitely a boon to instruction, but it should be overlaid atop the TSC.

A few years ago, Colleen Allem moved to Mexico and began instructing there. As she was new to the language (Spanish), she struggled to instruct SuperSlow and resorted to TSC. She resisted this as she considered TSC a lazy way to instruct.

Being more-or-less forced to instruct TSC, she found it to be a better instructional conveyance due to its reduction of detail. She was no longer required to convey corrections regarding the speed of motion or turnaround or alignment, and the subject was far less prone to engage in a myriad of discrepancies precipitated by the dynamic SuperSlow protocol.

TSC offers detail reduction so that the subject—especially the novice subject—can absorb immediately and act on the most crucial information. In other words, the subject’s mind is less swamped than with the SuperSlow.

With TSC, less means more. By reducing the need to verbalize many details, TSC allows the subject to work better with the fewest details that are absolutely required.

Analog FS, in some ways and for some situations and subjects, offers superior learning facilitation. However, TSC remains as the superior mode for minimalist sensory dependency. Only with TSC, can the subject completely close his eyes and most thoroughly internalize.

TSC is the King of Reductionism.

But still, TSC will probably hide the real process and the desired objective. This is why drawing the stimulus thresholds on the whiteboard presentation is crucial. It must be emphasized that the process of fatiguing the involved muscle as deeply as possible is necessary to guarantee attainment of the desired objective. This is the properly oriented target for the achievement oriented.

[Note: Throughout this discussion, I use target in a general sense and is not to be confused with the target load in an FS exercise.]

To repeat, during exercise, it is important to be achievement oriented. The problem, though with exercise, is that the orientation is obscure. It’s not obvious. And it is easy to mistake the desired objective as something with which the subject is already familiar.

With exercise, the ubiquitous pitfall is to confuse demonstration of the desired objective with the process of obtaining the desired objective.

We must not exercise as though we are at the carnival to swing the hammer to make the bell ring on the high striker. Your body does not know or care if you ring the bell. It only responds to the fatigue that sets in as you repeatedly swing the hammer to the point that you can longer ring the bell or to the point that you can no longer lift the proverbial hammer.

[And from my analogy, don’t get the idea that swinging an implement is a good means to exercise.

Brenda Hutchins’ office in a Nautilus fitness center (owned by Jim Flanagan) was near a Nautilus Neck and Shoulder machine, a machine used for performing shoulder shrug (trapezius) exercise. She often heard the dinging of the weight stack hitting the top of machine’s frame as men abused the exercise by moving fast and leaning backwards. This was an extreme example of externalization.]

In the simplest terms for my mental approach to an exercise, I say to myself, “I am here to exhaust this muscle. I am successful IF I temporarily make it incapable of function.” This is the real process.

[During the Nautilus Osteoporosis Study (1982-1986), it was common for a subject to whine, indicating the intolerable burning in her thighs as she was performing leg press, then stand out of the machine and walk across the room as if she had done nothing. This indicated her paltry inroad.]

This provides the best chance that the desired objective (strengthening stimulus) is attained. And if I then allow the body adequate recuperation, the purpose (strengthening) will follow.

Obtaining more muscular strength is the general objective of exercise. And we naturally wish to see this in demonstration as a reinforcement for our effort. This is yet another challenge for the instructor. And the ways to practically and safely demonstrate improvement are varied, personal, and specific to the context of the subject’s life.

But the demonstration of strength has nothing to do with the process of acquiring it.

Resistance Progression

During the Nautilus heyday, we promoted progressive resistance exercise (PRE). This phrase emphasized that the load applied to the body needed to be increased as the body became stronger in order for the body to be continually challenged.

On its face, PRE was a valid concept. However, as a natural proclivity of those who took the idea to heart, PRE was almost never viewed in reverse… that the resistance should be decreased as the body became weaker or should be decreased as the subject became adept at stricter performance of the exercise or should be decreased if the subject could not perform with proper form.And indiscriminate resistance increase, more often than not, greatly decreases competence of exercise performance.

PRE thus became a misstep in the promotion of inroad conditioning. It served as a major bridge in the evolution of our thinking (writing). It was a bridge similar to so-called resistance exercise, but not as blatantly sophomoric.

In my early years of enlightenment about exercise, I acknowledged—like so many others did and do—that weight training produced far better results than did running, swimming, and calisthenics. Since running, swimming, and calisthenics provided no resistance (a false impression) and weight training exclusively did (another false impression), I, like others with this experience, adopted an inappropriate name (resistance exercise) to underscore the distinction when resistance is not at all distinctive.

The important distinction BETWEEN weight training (when performed properly) AND running, swimming, and calisthenics is NOT the resistance. It is inroad.

Inroad is poorly obtained with running, swimming and calisthenics (and almost all other activities popularly deemed exercise). And inroad is potentially excellent with weight training.

Eventually, I managed to cross this first bridge (getting past the resistance exercise linguistical nonsense). However, the PRE bridge remained unacknowledged, although I largely ignored it as well as inadvertently chipped away at it all along the way.

The legitimate mention of PRE is perhaps to combat those who apply inroading tools with a steady-state mentality. For example, it was common for many years (and still is) for a woman to use a resistance in each exercise that permitted performance indefinitely… wherein little or no inroading occurred. Still, PRE is not exactly the concept to apply in this case.

Also, PRE was a subtle buttress against those who erroneously regarded as meaningfully progressive such approaches as running farther and/or faster OR increasing the grade of a treadmill OR swimming with drag suits and/or hand paddles OR walking with heavier backpacks and/or ankle weights OR riding a bicycle ergometer with tighter tensioning.

And while we around Arthur Jones acknowledged weightlifting (not proper weight training) as actual weight throwing (albeit directed vertically and upwards), discus, shot put, and javelin events are more obviously throwing. And less obviously throwing are the high jump and the long jump. We throw a lot of things it seems.

And as I have hammered for decades, all these endeavors involve resistance. And they can be made progressive, but not conveniently, safely, and efficiently so except for weight training.

Convenient, safe, and efficient progression of the ubiquitous resistance is a big improvement, but progression is merely a mechanism to engage the Real Process—inroad. And inroad is not totally dependent upon progression. In fact, TSC provides for no objective progression while offering the potential for the most efficient and safest inroad.

What’s more—especially when acknowledging that most acolytes of Arthur Jones and Nautilus associate resistance exclusively with a barbell or a weight machine of some kind—inroad does not require resistance or progression. In other words, inroad can occur without externally mediated resistance (apparatus derived). It, as Siciliano seemed to say, can be mediated from within the body in some cases—the body opposed to the body, one’s muscle against one’s muscle.

The correct concept is inroad-appropriate resistance. Obviously, this phrase indicates that the chosen resistance is one that elicits a meaningful inroad in an appropriately short time. I prefer Gus’ phraseology that the resistance is curated.

In other writings, I have shared the story of Arthur Jones when supervising a large bodybuilder (among several) wherein when the bodybuilder achieved a point of exhaustion in an exercise while exhibiting atrocious form, Arthur responded by adding more weight and demanding continuance of the exercise.

I was so disgusted and embarrassed at seeing this, I blocked the observation of this spectacle to a close friend who later sneaked past me. He later admitted that he had managed to view the workout and completely understood why I had blocked his observation of it.

A widely believed notion of PRE is that, as a principle of exercise, one should always strive to increase the resistance. This idea is abominable.

The Definition:

Exercise is a process whereby the body performs work of a demanding nature, in accordance with muscle and joint function, in a clinically controlled environment, within the constraints of safety, meaningfully loading the muscular structures to inroad their strength levels to stimulate a growth mechanism within minimum time.

Yes... "effort" and "work" are roughly interchangeable especially when work can be metabolic and/or physical work.

As I explain in the "Music and Dance" book, "work of a demanding nature" serves as the general preamble to the definition which is then further elaborated by the qualifiers, process, and purpose of the definition.

And yes, it is about growth. "Growth" can be mistaken to be only in terms of size (enlargement), but there are several kinds of growth. They might include greater vascularization, enhanced innervation in several possible ways, enhance metabolism, greater bone density. Many of these possibilities are a kind of growth that are not revealed as increased size.

Time is crucial. Just as in the reciprocity of film and other chemical processes. The human body is a chemistry plant. The exposure must be long enough to effect the stimulus and as brief as possible to avoid insults to the recovery system.

Thanks so much for your questions. Obviously, I require the elaborations I make in my books to delve more deeply into these nuances.

Thank you Ken. Much to digest here, but so far this is my favorite bit. "In the simplest terms for my mental approach to an exercise, I say to myself, “I am here to exhaust this muscle. I am successful IF I temporarily make it incapable of function.” This is the real process."